A Brief History of Canadian Equity Markets

Historically, stock exchanges have been the dominant venue for trading equities in most places throughout the world. Before 2001, the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) was the only senior equity marketplace in Canada. In the 1990s, market participants began to express concerns that the TSX’s monopoly status reduced its incentive to innovate, referencing the fact that the TSX’s technological capabilities lagged behind Alternative Trading Systems (ATSs) in the United States. At the same time, regulators were receiving requests from U.S. trading venues to launch their platforms in the Canadian market. (Bank of Canada Review).

By 2001, Canadian regulators has put more liberal ATS regulations in place. Additionally, advances in technology had decreased the barriers to entry for new trading venues. As such, new trading platforms began to open in Canada. (Bank of Canada Review). In 2006, New York based Liquidnet opened its Canadian branch. Different from the previous ATSs that had been launched in Canada, Liquidnet was Canada’s first “dark pool.” (Globe and Mail).

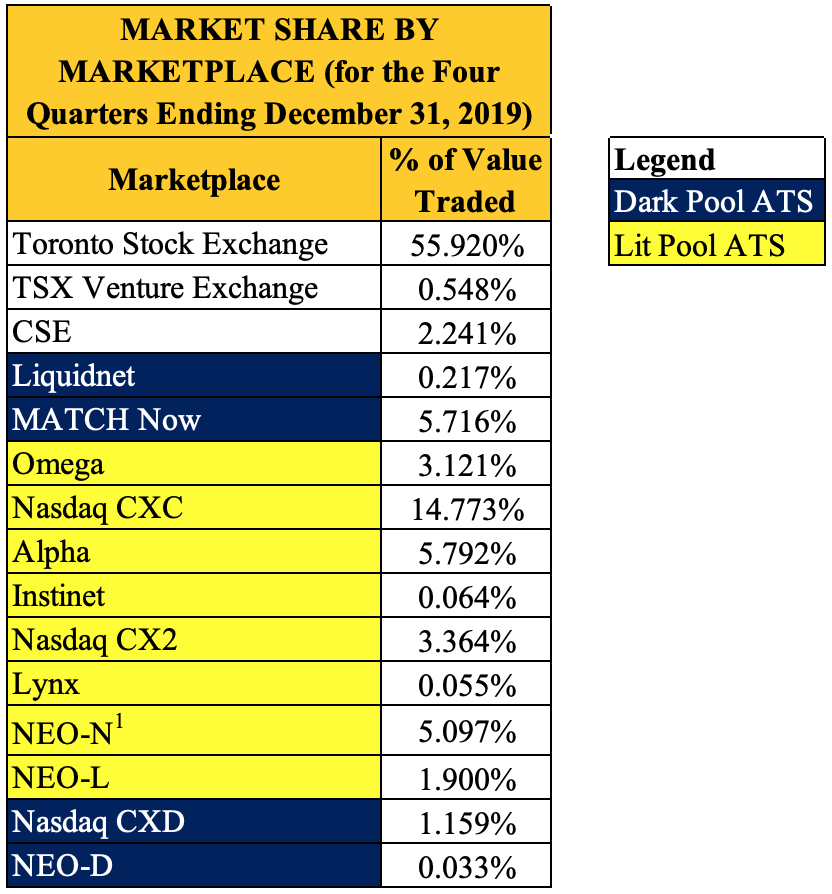

Since 2007, ATSs have been taking more and more market share from stock exchanges. As of December 2019, trades on ATSs (both dark and lit) accounted for 41.3% of total value traded on all Canadian marketplaces, with dark pool trades alone accounting for 7.1%. (IIROC).

What are Alternative Trading Systems?

An alternative trading system (ATS) is a venue that is not regulated as an exchange; instead, it is typically registered as a broker-dealer. An ATS matches the buy and sell orders of its subscribers. (Investopedia). In contrast to exchanges, which list securities and monitor the reporting of listed companies, ATSs do not list securities; they are simply a venue to trade securities that are listed on other marketplaces (TD Report).

A Deep Dive into Dark Pools

Dark pools are a type of ATS. Dark pools are characterized by a complete lack of transparency. In contrast to an exchange, where the order price, order size, and identity of the broker are visible to market participants, dark pools do not reveal any of these characteristics. Instead, an order sits invisible in the dark pool until it matches with the other side of the trade.

“One of the main advantages for institutional investors in using dark pools is for buying or selling large blocks of securities without showing their hand to others and thus avoiding market impact as neither the size of the trade nor the identity are revealed until some time after the trade is filled.” (Wikipedia).

Dark pools have become a controversial subject, especially following the release of Michael Lewis’ book Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt. Lewis argues that dark pools allow sophisticated high-frequency traders (HFTs) to exploit the system and front run ordinary investors. (International Business Times).

“Here’s an example: a high-frequency trading firm places bids and offers in small lots (like 100 shares) for a large number of listed stocks; if an order for stock XYZ gets executed (i.e., someone buys it in the dark pool), this alerts the high-frequency trading firm to the presence of a potentially large institutional order for stock XYZ. The high-frequency trading firm would then scoop up all available shares of XYZ in the market, hoping to sell them back to the institution that is a buyer of these shares [at a higher price].” (Investopedia).

While this is certainly a problem for unsophisticated investors with limited trading power, large institutional investors have developed strategies and algorithms that enable profitable trading despite the presence of HFTs in dark pools. For example, traders can designate orders as “Fill or Kill,” meaning that the entire order must be filled or else it will not trade at all. This eliminates the problem of HFTs detecting large blocks in the dark pool using small lots, since those small orders would not fill.

As mentioned above, the primary way that dark pools create value is by limiting the market impact of large orders. Let’s say an institutional investor were trying to sell its large stake in company XYZ on the TSX. Other market participants can see the details of the offer (including the seller’s identity), and since the institutional investor is known to be sophisticated, other investors might interpret the block sale as a sign that XYZ’s stock price is about to decrease. This would result in a rapid sell-off as investors try to unload their positions. The stock price would suffer, and the institutional seller would no longer have any hope of selling its stake at the original offer price. A dark pool significantly reduces the market impact of large orders, since it is less likely that market participants will find out about the order until after it is filled.

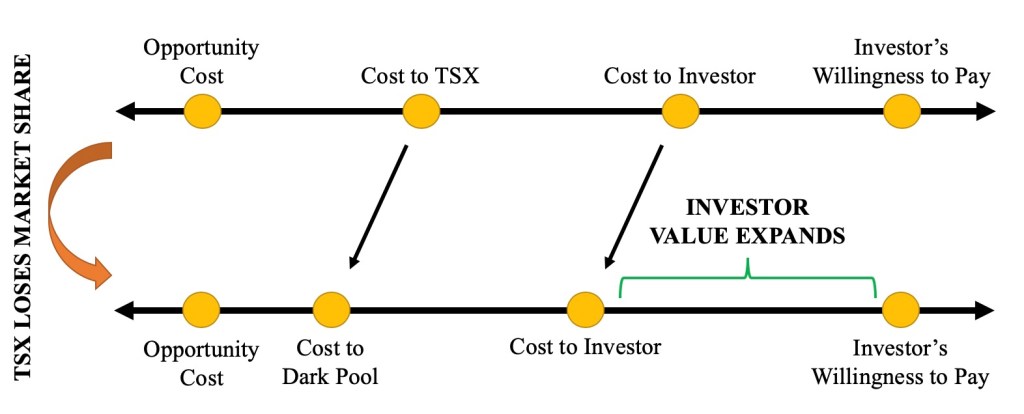

Another way that dark pools create value is by unbundling the services provided by an exchange. Since dark pools offer fewer services than an exchange (no listed securities or regulatory duties), they are cheaper to operate, therefore are able to charge lower trading fees.

Lastly, dark pools create value by improving liquidity. Since dark pool members are institutional investors with large orders, there is a higher likelihood of finding a counterparty with whom a large block can be crossed.

Upon their introduction to the Canadian market, dark pools represented a type of disruptive innovation. While the technology required to launch an ATS already existed, ATSs and dark pools resulted in a brand new business model and completely disrupted the Canadian equity market. Instead of paying sell-side brokers to trade their orders on exchanges, institutional investors were able trade their own orders directly on ATSs. In response to this innovation, exchanges have started to launch their own ATSs. For example, Nasdaq, the second largest stock exchange in the U.S., now competes with the TSX for market share with its three Canadian ATSs (1 dark, 2 lit). As ATSs continue to grow in popularity, more and more players are entering the market, differentiating themselves in fee structure and order routing methodology.

With ATSs disrupting exchanges and computer algorithms replacing human traders, one has to question what this will mean for sell-side banks. If institutional investors can trade directly through ATSs without the need for a broker, will we need sell-side brokers at all? The future of the Canadian equity market seems as opaque as the dark pools that disrupted it.