The practical implementation of decentralization in systems has been around from the early days of industrialization, even though the official coining of the term and its study are far more recent. The Mumbai dabbawala story is a testament to the concept of decentralizing processes without the use of modern technology. A key aspect of study warranted by the Mumbai dabbawala story is that most efficient systems are a mix of centralized and decentralized processes. For example, in a computer network, where the highest priority is tracking the flow of data (and not the data itself), it may make sense to make data traffic logs a decentralized process – distributing the risk of failure, processing power requirements and spreading the overall responsibility across multiple nodes. However, not all functions of that network need to be decentralized, for example, a central server may command the nodes on when and who to send data over the network. This system is a blend of both centralized and decentralized processes, and often in the real world, which is heavily ridden by constraints, this hybrid process structure makes most sense.

The Dabba Economics

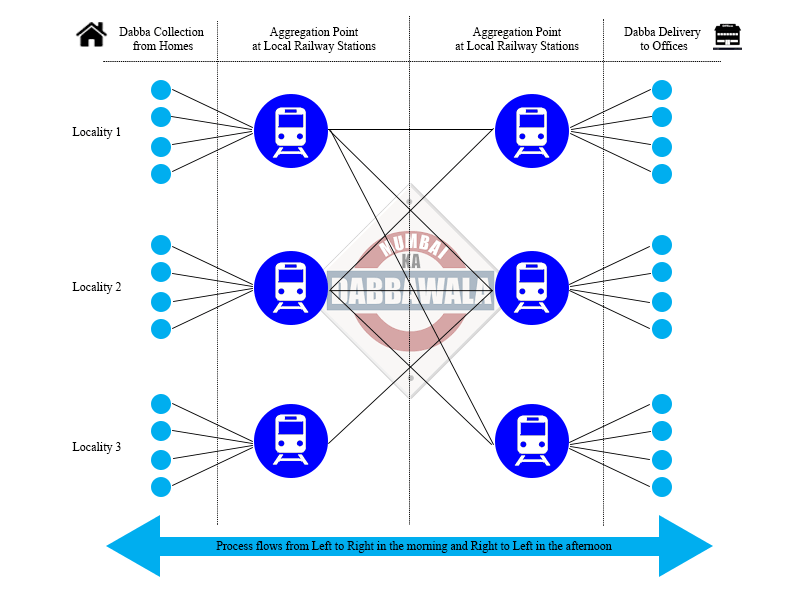

Founded in 1890, the dabbawala service is legendary for the sheer size and reliability of its operation. The need for a city-wide lunch service manifested itself with the rising population of Mumbai and the lack of an effective system to feed the rising number of workers at lunch time. The system was created by Mahadeo Havaji Bachche where he used the concepts of shared economy and self-organization to mobilize the porter services at railway stations along with bicycle delivery men from across the city to build an efficient logistics network that used a combination of railway lines to transport dabbas over large distances and distributed bicycle delivery networks to provide last mile collection and delivery from railway stations to nearby localities. The increase in population numbers also led to an increase in the number of unemployed workers in the city was quickly identified as a resource to produce home cooked meals and many of these people were incentivized to participate in the system because it was easy income and an infrastructure already existed to transport the food. The working population who had food cooked at home but preferred to travel without their lunch owing to the crowded trains and would typically have the dabbawalas pick up their food from home and deliver it at their place of work for convenience.

Centralization or Decentralization

The bicycle dabbawalas have always been responsible for the management of their own customers and pick up dabbas from the customers in their locality (enabling last mile collection and delivery) – this is a completely decentralized operation and uses self-employed entrepreneurs as dabbawalas. These dabbas are then taken to the local railway station where they are sorted and reorganized by their destination – this is central for every locality but happens across multiple localities. So, in a way, it is both a centralized and a decentralized process, depending on which lens we look at it from. It is interesting to note that most of the dabbawalas are uneducated workers and unable to read or write. They employ the use of a color-coded system to identify the source and destination of each dabba for organizing their delivery batches in record time. From here the dabba batches are transported across local trains from their source station to their destination station and are distributed to their final delivery address using local bicycle dabbawalas. This entire process is played out in reverse after the lunch hour and the empty dabbas are returned to their source address.

The complete operation is controlled by the union of dabbawalas which allows new stakeholders to invest and participate in the business. The union membership guarantees each dabbawala a minimum monthly wage and a lifetime guarantee of a job. The organizational structure is flat where every union member is paid the same wage, regardless of their age (18 or 65) or their capacity to lift weight. It is owned and operated by the same group of people and is the flattest organizational structure of that scale in India and possibly the world.

So What?

What started as an operation with a few hundred dabbawalas now engages over 5000 independent dabbawalas to distribute and collect around 130,000 lunch boxes everyday – that is 260,000 physical transactions. It is estimated that this system makes less than one mistake every eight million transactions and has such a minimal cost structure that in over 130 years of its existence, not a single rival has reached the scale or cost efficiency even nearing that of the dabbawalas. They remain as relevant today as they were a hundred years ago without the need of new IT systems or even phones.

While new decentralized technologies continue to emerge, the underlying ideas of distribution of risk and accountability are ancient concepts. Blockchain is one such manifestation of these ideas and carries the burden of its own limitations. The key to improving operations is not simply to use the latest in technology because its available to us, but rather to analyze the system and its constituent processes to answer one simple question – Why does decentralization make sense here?