Mariam Bibi lives in a village in one of the most impoverished provinces of Pakistan i.e. Sindh. She suffers from acute poverty (below the poverty line of $1.90 a day). Living in a remote village and a conservative society just adds to her challenges, and she can barely access appropriate health services – which is even more important during times such as pregnancy. Except for Karachi and Hyderabad, most cities in the province lack health care services, and it is even worse for those living in village in interior Sindh. To contextualize the plight of the underprovided in Pakistan, it is pertinent to note that the country ranks at 152 out of 189 in terms of Human Development Index[1]. There are many women like Mariam globally who lose their lives daily because of inadequate preventative and prescriptive health care services. Should people be left insulated from basic facilities to lead a ‘normal life’? Apparently, state structures have failed to fill the gap.

Weak economy and institutions have rendered the public health care system in shambles. The health care spending is barely 3%[2] of the GDP, which is way below the average of 7-8%[3] in the developed world. Add to it the general levels of corruption, and one can understand the inadequacy of service delivery. Several other factors such as lack of education further exacerbate the problem because there are not enough doctors to serve the people. Pakistan is the sixth most populated country in the world with approx. 200 million individuals. The number of physicians are less than 1 per 1000 people, which lags behind the average physicians in the developed world (around 3)[4]. The cultural layer makes the problem even more disastrous, as many women doctors end up leaving the profession after getting married. For years, technocrats in the developing world have been unable to address the health care challenge in their respective countries. However, the recent technological advancements do offer a solution.

doctHERs is a start-up in Pakistan looking to take on this challenge, and solve the country’s health crisis through tele medicine. The model is to establish health clinics in the underserved areas, where the people like Mariam can seek advice with regards to various health issues. Historically, many doctors resist to work in these areas or government just does not have the infrastructure to provide medical facilities. Through this solution, the setup costs are reduced drastically, and the doctors can treat the patients remotely. The trend is buttressed by the growing smart phone penetration – Pakistan also has one of the lowest data rates in the world. Which means that connecting these remote areas through the internet is well on its way, and is likely to intensify in the coming years. With that, even the infrastructure costs could be avoided because people can access the doctors through their devices. People like Mariam, who are living in extreme poverty can leverage the kinship networks to connect online through family or other people in the village (who are likely to be smart phone users). On the supply side, it has many implications. The government can leverage doctHERs or create a similar platform of its own – making public health care services accessible to people in the remote areas at relatively no additional cost. Secondly, this model can allow many women doctors reenter the profession as they will be able to work from home – balancing their professional and family responsibilities.

Similar to Pakistan, many entrepreneurs in the developing world are coming up with similar start-ups to fill the gap in the health care service delivery. It has obvious benefits, because it is low cost, and in the long run can reduce the burden on the system by dispelling adequate preventative care. It has the potential to revolutionize the existing service delivery structure. Most of the systems across the globe subscribe to a traditional model whereby clinics and hospitals are established at the local level, directed by the policies made at the national, provincial and district level. Owed to the differences in economic development, the health care provision suffers from regional variations – with the more affluent municipalities or provinces offering more elaborate care to their respective residents. The new model is democratizing the service delivery whereby the public sector physicians can treat the patients remotely, and private sector doctors can make additional income by getting on to the platform. Also, many of these platforms will be able to collect a lot relevant patient data that can be shared across platforms and transform the medical record keeping. The government can make use of this data to introduce targeted programs. For instance, if in a particular region, there is an observable trend of heart disease, the resources can be moved accordingly. From an economic point of view, it will lead to an efficient use of resources, in turn increasing the overall benefit to the society.

Moving forward, this decentralized structure of service delivery has a major potential to uplift the living standards of people across the globe – specifically those living in the poorest regions like Africa, South Asia and some parts of South America. The system can be expanded to give the underprivileged access to best medical advice in the world, as a person living in the remote area of Sahara desert can have access to a capable physician in the US or elsewhere. It is also relevant with regards to diseases like HIV and Cancer, where the local physician may not have an expertise in. Thus, it can be instrumental in taking the second or third opinion. In the coming decades, communications revolution will continue and the access to the internet would increase further. We have a strong reason to hope for a time where Mariam is not deprived of her basic right as a human i.e. access to health facilities, and that her kids live in an era where their mother is informed enough to take proper care of their health and wellness.

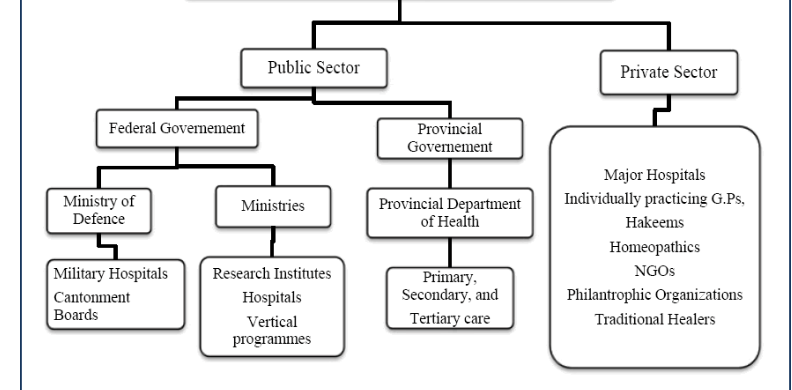

EXISTING SERVICE DELIVERY MODEL IN PAKISTAN

PROPOSED MODEL

[1] http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/PAK.pdf

[2] https://www.who.int/countries/pak/en/

[3] https://www.statista.com/statistics/268826/health-expenditure-as-gdp-percentage-in-oecd-countries/